Starting a Mine is Harder Than You Think.

Permitting, Jurisdictional, and Social Risks for Junior Miners

Introduction: The Path of Junior Mining

The global mining industry relies heavily on junior mining companies, a segment overlooked by the broader public. These entities, typically characterized by small market capitalizations (under $500 million) with a substantial portion falling below $10 million, are at the forefront of mineral discovery. Their primary focus is on the early, high-risk stages of mining development, which consists of exploration, discovery, resource definition, and scoping, with a significant emphasis on drilling activities to discern whether there are potentially mineable resources. However, junior miners not possess the infrastructure to build and operate their own mines. Instead, their objective is to identify and define economically viable mineral deposits, then to sell or joint-venture the project to or with major miners. This role is critical for the long-term health of the industry, as, similar to the role that the venture capital eco-system in technology start-ups; in mining, juniors undertake the speculative, capital-intensive search for new deposits of precious metals, base metals, and increasingly, critical minerals like lithium and rare earth elements.

Despite their indispensable role in feeding the future mineral supply, junior mining companies operate in an inherently treacherous stage of the supply chain. Investing in junior mining stocks is widely considered speculative and carries a heightened level of risk compared to more established mining companies. This elevated risk stems from the capital-intensive nature of early-stage exploration and the high rate of failure in discovering commercially viable deposits. The stock prices of these companies are notoriously volatile and fluctuate wildly based on exploration results, commodity price movements, and overall market sentiment.

A fundamental aspect of their business model is a dependence on capital raising activities, primarily through the issuance of new shares via private placements. The market window for such financing can open and close abruptly, making capital attraction hopeless during market downturns. This reliance on external funding means that even projects with promising geological potential can struggle to advance if market conditions are unfavorable, creating a feedback loop where market sentiment directly impacts project viability. The current environment, marked by low liquidity and daily trading volume in the junior mining sector, reflects a prevailing uncertainty among investors. This inherent instability, despite their strategic importance, made us realise that there’s a critical need for a deep understanding of the risks that can catalyze their success or, more commonly, their failure.

Join us in helping you understand mining, minerals, and commodity markets at The Mineral Strategist.

The Complicated Business of Permitting and Licensing

The journey of a mining project is segmented into distinct stages:

At each of these phases, mining companies are confronted with a lot of regualtory risk, necessitating the acquisition of numerous permits and licenses. The duration of this permitting process can span several years, with significant variations depending on the project's location and complexity. A critical aspect of this landscape is that the onus falls on the operator to identify and secure every required permit; no single agency possesses a comprehensive awareness of all the necessary authorizations.

Key Permit Categories and Their Complexities

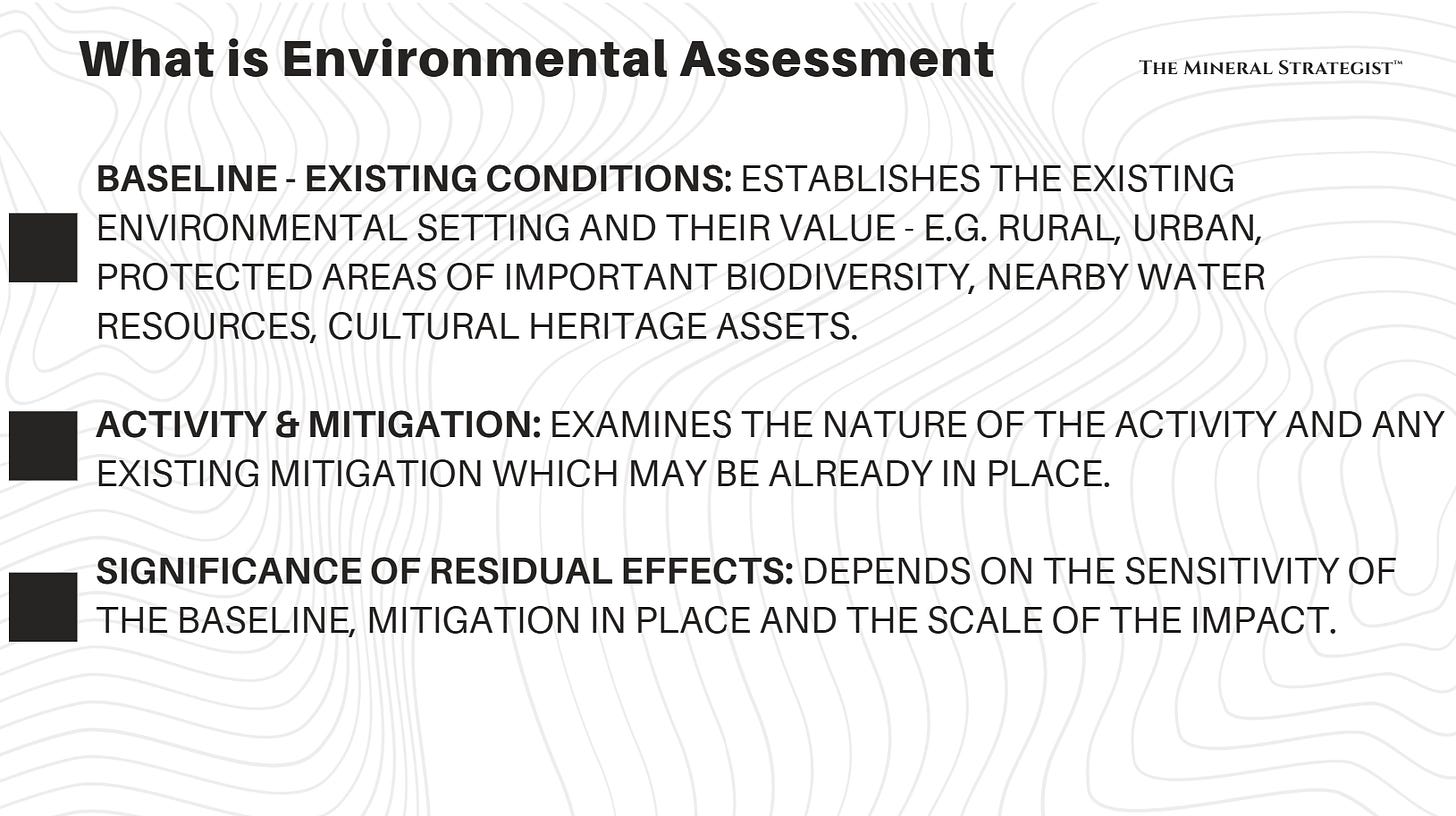

Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) and Approvals

Environmental Impact Assessments are foundational to modern mining, mandated to evaluate the potential environmental effects of proposed actions, including mine permit applications. In the United States, the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) governs these assessments, a process that can extend over several years. The permitting process for a mine typically commences with the collection of baseline environmental data alongside climatological data and cultural/historic resource analyses. A significant proportion of delays in critical mineral mine development, approximately 39%, are directly attributable to permitting issues, with 62% of these delays coming from stakeholder opposition or concerns regarding the project's environmental impacts. This transforms environmental compliance from a purely technical exercise into a substantial legal and social challenge.

Land Use and Access Rights

Mining activities involve land disturbance, requiring permits and authorizations from a multitude of governmental layers: federal, state, and local agencies, and in some instances, tribal authorities. In the United States, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), oversees vast tracts of federal land, managing them for sustained yield and multiple uses. However, recent regulatory shifts allow the BLM to designate extensive areas for "conservation leases" or even explicitly prohibit mining in certain regions, adding layers of complexity to land access. For federal coal mining on federal lands, a mining plan must receive approval from the Secretary of the Interior, highlighting another critical regulatory gate.

Water Use and Discharge Permits

Water management is a pivotal aspect of mining, with operations generating wastewater from mine drainage, mineral processing, and stormwater runoff. Compliance with effluent guidelines and the acquisition of National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permits are mandatory for managing these discharges. Furthermore, Water Use Permits (WUPs) are required to authorize the withdrawal of specific quantities of ground or surface water for various operational needs, including mining and dewatering. The issuance of WUPs can often be contingent upon the approval of other environmental permits, such as Environmental Resource Permits, and projects may face significant restrictions if located in areas designated as water resource concerns.

Health and Safety Compliance

Ensuring the safety and health of miners is very important and heavily regulated. The Federal Mine Safety and Health Act (Mine Act) mandates annual inspections by the U.S. Department of Labor's Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) to guarantee safe and healthy work environments. All mine operators and their contractors are required to adhere to specific safety and health standards, which include mandatory initial and annual refresher training for all employees.

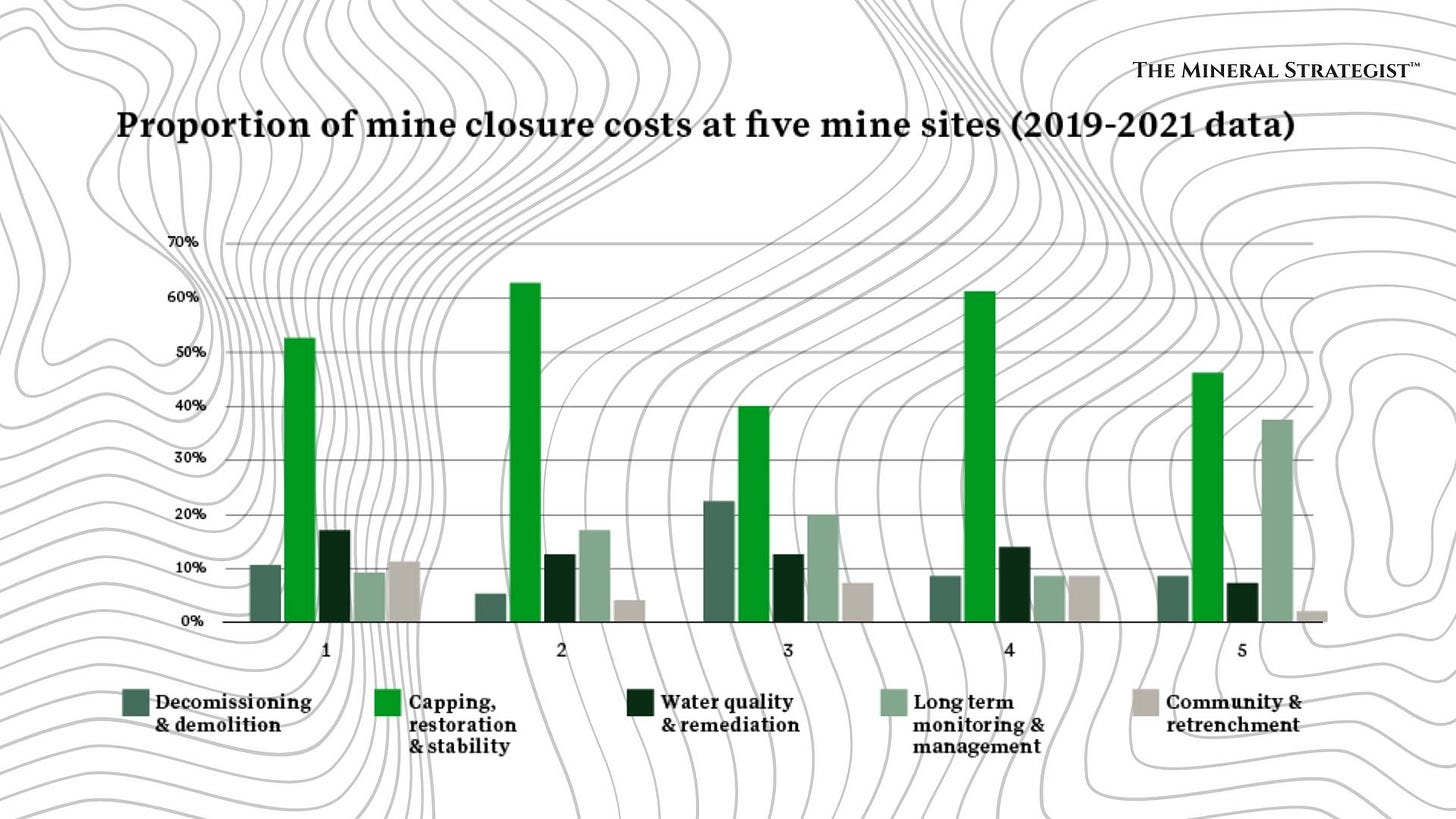

Mine Closure and Reclamation Bonds

The lifecycle of a mine ends in its closure, a process that is both complex and highly regulated. This phase requires specific permits and detailed plans for decommissioning, dismantling, and the comprehensive rehabilitation of the disturbed land. A standard requirement is for operators to post a financial assurance, typically a bond, to guarantee that reclamation costs are covered in the event of their failure to complete the work. The closure process involves a sequence of documents (Tentative Plan for Permanent Closure, Final Plan for Permanent Closure, Final Closure Report, and Request for Final Closure) all of which must be submitted and approved, with post-closure monitoring often extending for five to ten years or more.

The absence of a single, overarching authority or stakeholder that can provide a complete list of all necessary permissions means that companies must actively piece together this "permit puzzle". This fragmentation often leads to significant delays in project timelines, increased operational costs, and an elevated risk of non-compliance due to overlooked or misunderstood requirements. The reality is that the burden of identifying and securing all permits rests entirely with the miner, underscoring the critical importance of meticulous due diligence and proactive engagement with all relevant agencies from the outset.

Jurisdictional Risk

Jurisdictional risk encompasses the political, legal, and social uncertainties within a host country that can significantly and adversely affect mining projects. Junior miners are especially susceptible to this category of risk because they frequently conduct exploration and seek to develop projects in jurisdictions that differ from their primary listing or management location, often in regions with higher inherent social, political, or regulatory risks.

Drivers of Jurisdictional Instability

Political Shifts and Resource Nationalism

Sudden and significant political shifts, particularly in unstable or polarized environments, can negatively impact miners. A prominent manifestation of this is resource nationalism, defined as a government's assertion of greater control over its country's mineral wealth for strategic and economic reasons. This can take various forms, including the outright seizure of mining facilities, equipment, and resources belonging to foreign investors, the revocation of existing mining licenses, or substantial increases in mining taxes and royalties. It is observed that the frequency of license revocations tends to escalate when global mineral and metal prices rise, as host governments opportunistically seek to reclaim or renegotiate control over resources that have appreciated in value. A trend since 2014, for example, has seen 31 African countries reforming their mining codes to enhance government and local community participation, often introducing obligations for local mineral processing, stricter environmental and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) requirements, and higher royalties.

Corruption and Rule of Law Deficiencies

Corruption is a deeply corrosive risk that can directly impact miners through the solicitation of bribes or indirectly by distorting the broader business and investment climate. The absence or weakness of the rule of law, often characterized by a poorly funded, unprofessional, or politically influenced judiciary, creates profound uncertainty around the resolution of disputes, questions of mineral title, permitting approvals, and tax matters. Operating in such environments introduces an unpredictable element that significantly complicates long-term planning and investment security.

Geopolitical Dynamics and Trade Policies

Broader geopolitical shifts can also introduce significant jurisdictional risks. Changes in international relationships or the emergence of new industrial policies, such as the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act favoring critical minerals processed in the U.S. or countries with free trade agreements, can make investing in certain countries less attractive. The increasing influence of powers like China in some regions can intensify competition for mineral assets for Western companies, as Chinese entities often offer infrastructure lending and enhanced government-to-government relationships. While less common in recent decades, traditional political risks like outright nationalization, capital controls, and restrictions on the repatriation of profits continue to be latent threats that may resurface, particularly in an era of increasing resource nationalism and geopolitical fragmentation.

We made a post on changing laws in the U.S here:

The Imperative of Social License to Operate (SLO): An Unwritten Contract

Understanding SLO: Community Acceptance as a Non-Negotiable Asset

The Social License to Operate is an informal social contract that signifies the ongoing acceptance of a company's operations by the local community and other affected stakeholders. It is fundamentally different from a formal regulatory approval; it cannot be applied for, nor can it be bought. Instead, SLO is earned through consistent, transparent dialogue, genuine engagement, and the diligent building of trust with the community. For junior explorers, community engagement is no longer a discretionary activity; securing an SLO is now considered as vital as any technical exploration activity, such as geophysical surveys or drilling campaigns. The concept of "community" in this context is expansive, extending beyond immediate neighbors to include Indigenous peoples, local and regional governments, regulators, customers, suppliers, and even individuals with a cultural attachment to the land who may reside some distance from the project area.

The Impact of Community Opposition and Stakeholder Engagement

Companies that fail to secure or maintain an SLO frequently find themselves embroiled in prolonged legal battles. Community opposition often arises from legitimate concerns regarding potential environmental and socioeconomic risks associated with mining activities. The "Not In My Backyard" sentiment, where local groups dispute developments regardless of their apparent benefits, can be a powerful force against projects. Resolving such opposition is more likely when project developers allocate sufficient time for dialogue and relationship-building, genuinely address community concerns, and ensure that local benefits are clearly understood and maximized. Proactive, "political-style" campaigns, which involve identifying and mobilizing supporters and engaging in grassroots lobbying, are increasingly recognized as crucial strategies to mitigate opposition. Furthermore, formalizing commitments through Community Benefits Agreements can establish clear provisions for local employment, economic benefits, environmental standards, and long-term monitoring, fostering a more stable operating environment.

While governments grant legal permits, the acceptance by local communities, which constitutes the SLO, wields equally, if not more, significant power in determining a project's viability. A project may possess every necessary regulatory approval, yet still face insurmountable obstacles and ultimately fail if it lacks community acceptance. The Donlin Gold project in Alaska serves as a stark illustration: despite having federal permits, it has been stalled by court orders and tribal opposition due to its failure to secure a social license, directly impacting its ability to proceed. Similarly, the Pebble Mine project, also in Alaska, saw its Net Present Value (NPV) significantly diminish after accounting for the risks associated with stakeholder opposition, ultimately failing to achieve community consensus on environmental risks. These cases demonstrate that legal compliance, while necessary, is insufficient on its own to de-risk a project; the "unwritten contract" of community acceptance can effectively veto or severely impede projects, especially in jurisdictions where community rights are strongly asserted or the rule of law is weak.

Resource nationalism is a cyclical and opportunistic threat that intensifies with rising commodity prices and shifts in political ideology. When mineral prices increase, host governments may opportunistically seek to "repatriate resources" by revoking licenses or increasing taxes, aiming to capture a larger share of the newfound value. Junior miners are particularly vulnerable to this phenomenon due to their smaller size and lesser influence compared to major producers. This makes them easier targets for governments looking to renegotiate terms or increase state participation. The political shifts observed in Latin America, for instance, have intensified political risks for Canadian miners, with a broad march of the political Left often less favorable to foreign mining companies. This dynamic creates an environment where the economic and political landscape can shift rapidly, disproportionately impacting less powerful entities and making long-term investment planning highly uncertain.

Furthermore, jurisdictions characterized by unclear rules, weak enforcement, corruption, and an absence of the rule of law create a pervasive "governance gap" that severely undermines the predictability of permitting processes and legal outcomes. In such environments, institutional expertise for implementing assessment and permitting regimes may be lacking, leading to ambiguous or untested regulations. This ambiguity and inconsistency significantly elevates the risk profile for junior miners. It renders due diligence and risk assessment far more challenging than in stable, transparent environments, as the goalposts for compliance can shift without warning, leading to disputes over mineral title, permits, and taxation. This unpredictable governance environment can deter investment and prevent projects from progressing, regardless of their intrinsic geological merit.

Project Viability to Failure

The confluence of permitting, licensing, and jurisdictional risks acts as a powerful catalyst, fundamentally altering the trajectory of junior mining projects.

Financial Erosion

Permitting issues are identified as the single largest cause of delays for critical minerals projects, accounting for 39% of all postponements. These delays have direct and severe financial repercussions. They translate into unexpected costs, significant cash flow disruptions, and potentially incur expedited fees, higher labor costs, and penalties for missed milestones. When combined with escalating costs and increased risks, this can halve a project's expected value even before production commences, rendering it financially unviable.

This financial erosion is particularly devastating for junior miners, who are inherently capital-intensive and heavily reliant on external funding. Protracted delays and the associated increase in risk lead to a deterioration in investor sentiment, making it exceedingly difficult for these companies to attract and secure the necessary capital for project development.

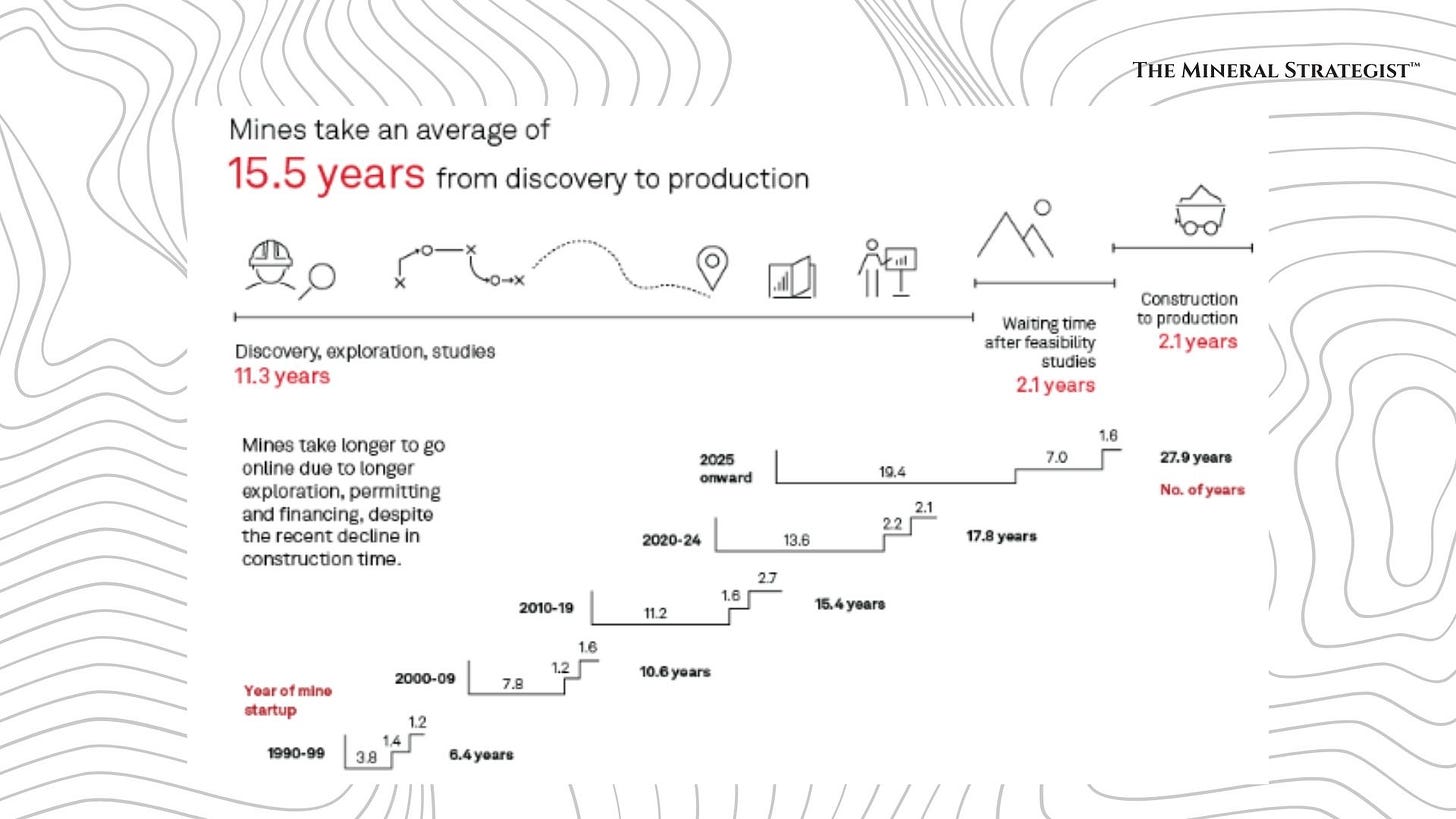

Timeline Derailment

The permitting process is frequently a significant bottleneck, leading to substantial timeline derailment. In the United States, for instance, obtaining mine permits can take an average of 7 to 10 years, a duration considerably longer than in other developed nations with similarly stringent environmental regulations, such as Canada and Australia, where the average is typically 2 to 3 years.7 This protracted process can cause projects to stagnate for years, preventing them from ever reaching fruition and forcing companies to miss favorable market windows for commodity prices or financing. Research indicates that over 40% of delays in critical minerals projects occur early in the development cycle, specifically at the feasibility stage. This early-stage vulnerability highlights a critical "feasibility trap" where projects, despite promising technical assessments, become ensnared in regulatory and social complexities before significant capital has been deployed, making recovery difficult

Operational Disruption

Beyond financial and timeline impacts, permitting and jurisdictional challenges can directly disrupt operational continuity. Delays often necessitate costly project redesigns, particularly if stakeholder concerns or environmental impacts were not adequately factored into the initial project design. Regulatory changes themselves are a significant operational risk, demanding constant adaptation and compliance. Furthermore, a lack of stakeholder buy-in, insufficient resource allocation, and poor communication can severely impede the effective execution of contingency measures during a crisis, exacerbating the impact of any disruption.41 In extreme cases, license revocations, whether due to non-compliance with terms or opportunistic governmental actions, can bring operations to an abrupt and complete halt.

The vast differences in permitting timelines between various countries create a significant competitive landscape. Jurisdictions with efficient, streamlined processes, such as Canada and Australia (averaging 2-3 years), offer a distinct advantage over those with protracted timelines, like the U.S. (7-10 years). This disparity directly influences investor attractiveness and the global flow of capital. For example, Chile's recent permitting reforms, which aim to accelerate mine approvals from 24-36 months to a more competitive timeframe, are poised to significantly improve return on investment metrics for shareholders and enhance the country's competitiveness as a mining destination. This demonstrates that regulatory efficiency is as crucial as geological potential in attracting investment and meeting the surging global demand for critical minerals. Capital naturally gravitates towards environments that offer greater predictability and faster pathways to production, making permitting speed a key differentiator in the global mining investment landscape.

Conclusion

This ‘premitting’ fragmentation and the often-protracted nature of environmental reviews can lead to significant delays and cost overruns. Environmental assessments, intended as a de-risking phase, frequently become chokepoints and sources of litigation, especially when stakeholder concerns are not adequately addressed early in the project design. While political will can, in specific instances, accelerate permitting for strategically important minerals, this does not alleviate the systemic burdens faced by the majority of junior mining projects.

Beyond formal regulations "Social License to Operate" (SLO) emerges as a non-negotiable asset. As demonstrated by projects like Donlin Gold and Pebble Mine, even with formal permits, strong community and Indigenous opposition can effectively veto a project. Legal compliance alone is insufficient; genuine community acceptance, built through transparent dialogue and proactive engagement, is paramount. Furthermore, resource nationalism, in particular, is an opportunistic threat that intensifies with rising commodity prices, disproportionately affecting smaller, less influential junior miners.

The catalytic impact of these risks is evident in the financial erosion, timeline derailment, and operational disruptions they cause. Permitting delays directly translate into substantial financial losses, diminishing project value and jeopardizing financing. The "feasibility trap," where early-stage stakeholder neglect leads to costly redesigns and delays, is a recurring theme. Conversely, jurisdictions with efficient permitting processes gain a significant competitive advantage, attracting investment and accelerating critical mineral supply.

For junior miners and investors. integrating dilligent Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) practices into project design from the outset can transform potential risks into competitive advantages, leading to smoother permitting and operational stability. Furthermore, thorough due diligence on a jurisdiction's political stability, regulatory transparency, and rule of law is critical. While some risks are inherent, a strategic approach that prioritizes early engagement, transparent communication, and adaptive compliance can significantly de-risk projects, enhance investor confidence, and ultimately improve the likelihood of a junior mining project transitioning from discovery to successful production.

If you enjoyed this post, consider subscribing to The Mineral Strategist.