Why Are U.S Mining Permits Exploding?

Easing Mining Permits In The U.S., Copper Supply Issues, Critical Minerals Dependence, Production Impact of FAST-41.

“The Trump administration has moved to amplify U.S. mining permits, unveiling streamlined environmental review timelines for 20 domestic mining projects under the FAST-41 initiative.”

In April and May 2025, officials added two waves of ten projects to the federal Permitting Dashboard, which is an online timetable for major projects. This was driven by the bid to reduce red tape and accelerate the development of critical minerals. This “fast-track” list spans everything from copper and lithium to potash, phosphate, gold, antimony and metallurgical coal.

By publishing coordinated schedules for environmental reviews, the administration aims to bring new mines into production years faster than the status quo, strengthen U.S. supply chains for batteries, electric grids, defense systems and other industries. The policy is a foundation of Trump’s broader strategy of “American Energy Dominance,” emphasizing resource independence and industrial revival . However, the initiative also raises questions: Will faster permits truly ease mineral shortages and attract investment? How does this deregulatory push compare to the previous Biden administration’s approach? And can the U.S. accelerate mining without igniting environmental backlashes? We will look at Trump’s FAST-41 mining program in depth – from the specific projects and metals involved to the market, policy, and ESG (environmental, social, governance) implications.

FAST-41: Easing Permits for U.S. Mines

FAST-41 refers to Title 41 of the 2015 Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act, a bipartisan law that created a specialized process to improve federal coordination and timelines for permitting large infrastructure projects . It set up the Federal Permitting Improvement Steering Council (FPISC or Permitting Council) to oversee interagency review of “covered” projects and established an online Permitting Dashboard to track progress. In essence, FAST-41 doesn’t eliminate any environmental requirements – projects must still complete all reviews under laws like NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act), but it imposes discipline by setting target schedules, forcing agencies to synchronize their work, and increasing transparency. The idea is that exposing the process will increase accountability and reduce the notorious delays and overlaps in U.S. permitting. Mining projects in the U.S. often see 7–10 year timelines for approval, far longer than the 2–5 years typical in countries like Australia or Canada. Such drawn-out timelines have been blamed for deterring investment, raising costs, and leaving America dependent on mineral imports. FAST-41 participation has been shown to potentially cut permitting times by roughly 30% through better project management.

Under Biden, FAST-41 had been used selectively – for example, South32’s Hermosa zinc-manganese mine in Arizona became the first mining project to get FAST-41 treatment during the Biden era. However, Biden’s usage generally limited FAST-41 to officially designated “critical minerals.” Now Trump, in his second term, has dramatically expanded the program via executive orders. In March 2025, Trump issued Executive Order 14241, “Immediate Measures to Increase American Mineral Production,” directing agencies to prioritize domestic mining and even broaden what counts as a critical mineral. Under this directive, the definition of critical minerals now includes not just the usual suspects like lithium and rare earths, but also potash and gold. Trump’s orders also called for an interagency list of priority mining projects that could be expedited. The result was the National Energy Dominance Council (NEDC) compiling a list of projects, which the Permitting Council formally added to the Dashboard as FAST-41 Transparency Projects in April 2025. Inclusion on this list means the project’s permitting timetable is now public and closely managed, though it “does not predetermine the outcome” of any decision or waive environmental laws.

Ten Fast-Tracked Mining Projects: Timeline and Details

On April 18, 2025, the White House and Permitting Council revealed the first tranche of 10 mining projects added to the FAST-41 Dashboard. These span a range of states, companies, and critical minerals. Some are brand-new mines in early exploration stages; others are expansions of existing operations or longstalled proposals now given “priority” status. The table below summarizes the ten projects, their locations, sponsors, target minerals, and where they stand in the permitting process:

These projects illustrate the breadth of the U.S. mineral portfolio being targeted. Copper features prominently with Resolution Copper in Arizona – one of the world’s largest undeveloped copper deposits – and the smaller Lisbon Valley mine in Utah, plus copper as a byproduct at Libby (Montanore). Lithium is another focus, the Silver Peak brine operation in Nevada (the only currently producing U.S. lithium source) is planned for expansion, while South West Arkansas represents a greenfield lithium brine project tapping the Smackover Formation and McDermitt is an early-stage lithium clay exploration on the Oregon-Nevada border. Fertilizer minerals are included via Caldwell Canyon (phosphate) and Michigan Potash, reflecting an expansive view of “critical” resources needed for economic security. Notably, some projects aim to revive historic mine sites – Stibnite seeks to reopen a WWII-era mining district with an extensive environmental cleanup component, and Hecla’s Libby (Montanore) project. While several projects (McDermitt, Libby, etc.) are still years from production and need exploration to prove out reserves, their FAST-41 designation “signals priority status” and puts agencies on a coordinated timeline going forward.

According to the Permitting Council, seven of the ten projects were already in advanced permitting (some nearing final decisions), two are in preliminary exploration stage, and three involve expansions of existing operations. The Dashboard listings for each now include a detailed timetable, with milestones such as draft Environmental Impact Statements (EIS), public comment periods, and target dates for final Records of Decision. For example, the entry for Hecla’s Libby project indicates a detailed schedule was to be published by May 2, 2025. This transparency is meant to reduce uncertainty. “Permitting timelines will now be coordinated among relevant agencies and tracked publicly to reduce administrative redundancies that have historically delayed US mining ventures for up to a decade,” notes the Investing News Network . In practical terms, a FAST-41 tag should help a company like Hecla or Standard Lithium anticipate when key permits might be in hand, potentially enabling earlier investment decisions (or at least fewer “unknowns” to scare off financiers). Companies have welcomed the move; as Hecla’s CEO said after Libby’s inclusion,

“This priority status…should help streamline the remaining permitting process as we move toward a final Record of Decision”.

It’s important to emphasize that FAST-41 status does not guarantee approval of these mines. But it does mean the federal government is effectively putting its thumb on the scale to push them forward with speed. Additional projects are being added on a rolling basis: in May, a second batch of 10 was announced, including a proposed copper-nickel mine in Minnesota (PolyMet’s NorthMet project), a uranium mine in New Mexico (Roca Honda), an expansion of a platinum-group metals mine in Montana (Sibanye-Stillwater’s Stillwater Complex), a silver mine in Alaska (Hecla’s Greens Creek) and a titanium heavy-minerals project in Georgia (Chemours). This brings the total to 20 fast-tracked mining projects nationwide, reflecting an aggressive push to diversify America’s mineral sources. “The latest 10 include a proposed copper and nickel mine in Minnesota... an Alaskan silver project... and a Georgia titanium dioxide project,” Reuters reported, noting that all are now on the public dashboard for tracking . The breadth of projects – from battery metals to fertilizer inputs – underscores the administration’s all-of-the-above approach to critical minerals.

Copper – Supply Issues

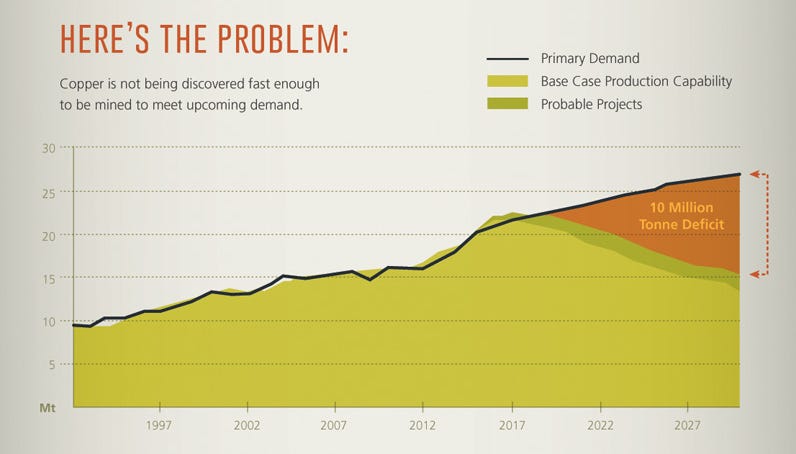

The U.S. has significant copper reserves on paper, yet domestic mine output has stagnated, covering only ~55% of U.S. consumption in recent years (the rest being met by imports). In 2024, U.S. net import reliance for copper was about 45%, with America increasingly dependent on Chile, Mexico, Canada and other suppliers. This trend worries policymakers because copper is essential for power grids, electric vehicles (EVs), renewable energy systems, and military technology. In fact, the Department of Energy added copper to its critical minerals watch-list in 2024, reflecting concerns that insufficient supply could bottleneck the energy transition. Global demand projections justify those concerns: Copper demand is projected to double by 2030 (and nearly double again by 2035), driven by EVs (which use 2-4x more copper than gasoline cars), massive expansions in transmission lines, solar and wind installations, and general economic growth . S&P Global analysts forecast that more copper will be needed in the next 30 years than was produced in the last 120 years . In short, a supply crunch is looming – a 2022 study warned of a 10-million-ton annual global shortfall by 2031 if new mines aren’t built.

Against this backdrop, the FAST-41 mining push targets some major copper opportunities. The crown jewel is Resolution Copper in Arizona. If developed, Resolution would be one of the largest copper mines in North America, tapping a giant deep deposit that Rio Tinto and BHP have been developing for years. At full production, it could supply up to 25% of U.S. copper demand – on the order of 500,000 metric tons of copper per year, which would significantly reduce U.S. import dependence. (For context, that is roughly equivalent to the entire annual copper output of the state of Arizona today.) Even more modest estimates indicate output of ~120,000 tonnes annually (about 7% of U.S. consumption) in earlier phases. Resolution alone could change the calculus of U.S. copper supply from current levels.

It “would reduce reliance on imports… by 15 percentage points,” notes one analysis.

No other single project on the horizon has such scale. However, it has also been among the most controversial – the proposed block-cave mine is situated beneath Oak Flat, a site sacred to the San Carlos Apache and other tribes, and it requires a land exchange that has been tied up in legal challenges. The Obama administration halted the project’s land swap in 2016, the Trump administration later approved the EIS and land transfer in early 2021, which the Biden administration then withdrew to allow more tribal consultation. Now, with FAST-41 and a renewed push, the project’s permitting is back on track, with officials eyeing a final Record of Decision possibly by 2026. But the outcome hinges on both legal decisions (a 9th Circuit court case on religious freedom is pending) and the ability of the FAST-41 process to resolve remaining environmental concerns (such as managing 1.5 billion tons of tailings and securing enough water in Arizona’s arid climate). Resolution Copper’s saga encapsulates the high stakes: it is a “high-stakes balancing act” – between supplying a metal vital to the green economy and respecting indigenous rights and environmental limits.

Other copper-related projects on the fast-track list are smaller but still notable. Lisbon Valley Copper in Utah is an existing open-pit mine that shut down in 2008 during low prices; its owner now seeks to restart it with an expansion into new copper oxide zones. The FAST-41 designation could help finalize permits for insitu recovery pilots or new pits. While Lisbon Valley would produce only a few thousand tons of copper annually, every bit helps given the tight market. Another project, Hecla’s Libby (Montanore) in Montana, is primarily a silver deposit but contains a substantial copper resource as well – estimated at 4 billion pounds of copper and 500 million ounces of silver under the Cabinet Mountains Wilderness . If Hecla eventually opens this mine (and its twin project Rock Creek), it could yield tens of thousands of tons of copper per year as a byproduct of silver. However, the Libby/Montanore project faces stiff opposition because it lies beneath protected wilderness; environmental groups point out the threat to sensitive ecosystems like alpine lakes, grizzly bear and bull trout habitat in the region . “I’m not naïve – I understand we need mining to support our modern life – but this is literally underneath a wilderness,” said one Montana environmental advocate, highlighting the tensions between resource development and conservation. Hecla has argued it can mine responsibly (pointing to plans to treat water and the project’s potential to create jobs in a rural area), but it will need to convince regulators and courts that Montanore can coexist with the wilderness above.

In terms of market impact, bringing new U.S. copper mines online would be significant for domestic consumers (wire and cable manufacturers, electronics, EV makers, etc.). The U.S. currently relies on Chile and Peru for refined copper; any disruption (strikes, political unrest, or Chile’s new higher royalties) can tighten supply and raise prices for U.S. industry. Analysts say the prospect of Resolution Copper and others advancing is being watched closely by the global market – though these projects won’t produce copper for several years at best, their progress could slightly temper long-term deficit forecasts and influence investment elsewhere. Copper prices have been strong (around $4–4.5/lb in 2025), reflecting an 80% rise since 2016 amid EV demand and supply bottlenecks. If U.S. projects falter, the supply gap could worsen, potentially driving prices even higher toward the $5–6/lb range that would pressure manufacturers (Goldman Sachs even forecast a possibility of $15,000/tonne copper in a bullish scenario). Conversely, if fast-tracking succeeds, it could encourage more exploration in U.S. copper districts – e.g. the revival of Arizona’s other big copper project (Rosemont), or new porphyry discoveries in Nevada. The National Mining Association has argued that unlocking domestic copper is essential not just for economics but for geopolitics: “With copper demand projected to double by 2030... the U.S. is facing a supply crisis that could stifle growth and leave us unnecessarily dependent on foreign imports unless we act now to unlock our domestic reserves” . The Trump administration’s mining initiative is clearly aligned with that view, aiming to turn rich U.S. copper deposits from untapped potential into producing assets in time to meet the demand of the 2030s.

Lithium – Building a Domestic Supply Chain

Lithium is another linchpin of the critical minerals strategy, given its role in lithium-ion batteries for EVs and grid storage. Only one lithium mine operates in the country (Albemarle’s Silver Peak brine operation in Nevada), which produces roughly 5,000 tonnes of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE) per year – enough to meet perhaps 1-2% of global demand. As a result, America is heavily import-reliant: from 2016–2019, over 90% of U.S. lithium imports came from Argentina and Chile. Overall import dependence was about 50% in 2020 (the remainder of U.S. lithium supply coming from Silver Peak plus some recycling). Since then, lithium demand has skyrocketed with EV adoption, likely increasing U.S. reliance further (especially as domestic battery plants ramp up). China controls much of the lithium processing and battery supply chain. This vulnerability is why lithium is of importance in the U.S. critical mineral policy. The Biden administration invested in lithium projects via the Defense Production Act and DOE grants, and the Trump administration’s current push is doubling down on boosting domestic lithium output.

Among the 10 fast-tracked projects, three are lithium-focused: the Silver Peak expansion in Nevada, South West Arkansas (SWA) lithium project, and the McDermitt lithium exploration in Oregon. Each represents a different approach to lithium supply:

Silver Peak (Nevada): This is the only producing U.S. lithium source today, extracting lithium brines from Clayton Valley and evaporating them to produce lithium carbonate. Albemarle announced plans in 2021 to double Silver Peak’s capacity from ~5,000 to 10,000 tonnes per year of LCE by 2025. That expansion requires permits to drill new brine wells and expand processing infrastructure on public lands – now being fast-tracked by BLM. Albemarle’s CEO recently emphasized that “Silver Peak’s expansion to 10,000 tons by 2026 aligns with [our] long-term outlook”, highlighting its strategic value. 10,000 t/yr is still relatively small (Tesla’s Nevada Gigafactory alone could consume many times that if running at full capacity). But, every tonne from Silver Peak displaces a tonne of import, and Albemarle is also evaluating new technologies (like direct lithium extraction and clay processing) in Nevada to further boost output.

South West Arkansas (SWA): This project is a partnership between Standard Lithium – a U.S. lithium development company – and Equinor, the Norwegian energy company, targeting the lithium-rich brines of the Smackover Formation in southern Arkansas. SWA plans to use modern Direct Lithium Extraction (DLE) technology to pull lithium out of brine more quickly and reinject the spent brine underground. The project envisions a commercial plant producing 22,500 tonnes per year of battery-quality lithium carbonate by around 2028. It’s roughly equivalent to 15–20% of current U.S. lithium consumption (though by 2028 demand will be higher), and would establish an entirely new U.S. lithium-producing region. The FAST-41 status here is notable because the lead agency is actually the Department of Energy (DOE), implying the project might involve federal loan guarantees or R&D funding that trigger NEPA review. In April 2025, the White House advised the SWA project as a key example of expedited critical mineral permitting. Standard Lithium’s team welcomed the news; the company has already been operating a demonstration plant in Arkansas for a couple of years, and just in late April received a state regulatory approval for its first production brine unit. “Gaining regulatory approval for our first brine unit is an important step in our project timeline… we continue momentum with the SWA Project,” said Standard Lithium’s President in reference to that milestone . In other words, things are moving – the company is marching toward a final investment decision, and the FAST-41 timeline transparency will help it coordinate the remaining federal permits (likely related to injection wells, environmental impact assessments, etc.). If all goes to plan, by the late 2020s Arkansas could be supplying a substantial volume of lithium for U.S. battery makers, reducing the need for imports from South America or Australia.

McDermitt Lithium (Oregon): The Oregon-Nevada border region is known to host large lithium clay deposits (notably Lithium Americas’ Thacker Pass project on the Nevada side). HiTech Minerals, a subsidiary of Australia’s Jindalee Resources, is proposing to drill up to 267 exploration holes in Oregon to delineate lithium resources. The BLM has fast-tracked the Exploration Plan of Operations under an Environmental Assessment, which was open for public comment in March 2025. This is essentially about gathering data; if the drilling proves a significant lithium deposit, a mine plan and full EIS would come later. By including an exploration project in FAST-41, the administration is signaling it doesn’t want early-stage bureaucratic delays either – even grassroots drilling permits should move quickly if they pertain to critical minerals. The McDermitt basin could hold one of North America’s largest clay lithium resources, so the strategic upside is high. That said, mining lithium from clay is technically challenging (no one has yet done it at commercial scale). Lithium Americas’ Thacker Pass (Nevada) is aiming to be the first, starting production by 2026; if that succeeds, it could pave the way for similar clay projects like this Oregon extension. In the meantime, environmental activists and local tribes are already watchful in this area – Thacker Pass faced protests and lawsuits on environmental grounds, and the Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone have interests in the region. There is even a site in the caldera considered sacred (Thacker Pass/Peehee Mu’huh), so any expansion of lithium exploration is likely to attract scrutiny from Indigenous groups. FAST-41 or not, if the project advances to mine development, expect legal challenges reminiscent of Thacker Pass’s, which delayed that project by over a year.

From a commodity standpoint, more domestic lithium production cannot come soon enough for the U.S. EV industry. The global lithium market has been extremely tight: prices spiked to record highs in 2022 (over $70,000/tonne for lithium carbonate equivalent) before moderating, as supply struggled to keep up with demand from EV battery factories. Although new lithium mines are coming online globally (in Australia, China, South America), there are concerns of a persistent supply-demand gap toward the late 2020s as EV adoption accelerates. The U.S. in particular has set ambitious goals for EVs (50% of new car sales by 2030, according to Biden’s plans) which will require a massive scale-up in battery production – and thus lithium. Currently, the U.S. is essentially 100% reliant on external sources for processed lithium chemicals (even the raw material from Silver Peak is sent abroad for refining). 22,500 t/yr from Arkansas plus 10,000 t/yr from Nevada (Silver Peak) would together represent over 30,000 tonnes – roughly the annual lithium content for half a million to a million electric cars (depending on battery size). Other fast-tracked projects not yet on the list may join – e.g. Piedmont Lithium’s upcoming Carolina project or expansions in California’s Salton Sea geothermal brines. Of course, the viability of these projects is crucial: they must overcome technical challenges (DLE technology, clay processing), secure financing, and ensure environmental safeguards for water and land. But with high lithium prices and strong policy support (including the possibility of DOE loans or DOD funding under the Defense Production Act), the chances of success are better than ever. Investors have certainly taken note – Standard Lithium’s stock, for example, has been volatile but generally benefited from each positive permitting step, and the partnership with Equinor (a deep-pocketed ally) was interpreted as a vote of confidence in the project’s viability.

Antimony and Metallurgical Coal – Critical Minerals for the Industrial Base

The FAST-41 list also highlights antimony and metallurgical coal, two commodities critical to the U.S. industrial base, albeit for very different reasons.

Antimony is a metal most Americans have never heard of, yet it is vital for national defense and manufacturing. It is used in flame retardants, semiconductors, and perhaps most critically, in ammunition and ordnance. Antimony trisulfide is a key ingredient in primers for bullets, as well as in explosives and military flares. The U.S. has no primary antimony production today – they are 100% reliant on imports, with China, Russia and Tajikistan controlling ~90% of global supply. This supply chain proved vulnerable recently; in 2024, China imposed a ban on antimony product exports to the U.S. , raising alarm about access to the metal. Recognizing this, the Department of Defense has already invested in securing antimony: Perpetua Resources (developer of the Stibnite Gold Project) received over $70 million in DOD funding to support its permitting and feasibility, underlining the Pentagon’s urgency to re-establish a domestic source. Uniquely, Stibnite is being advanced primarily as a gold mine, but it contains significant antimony as a co-product – about 14% of the ore’s value. Once operational, Stibnite could produce 35% of U.S. antimony demand in its first six years, immediately making America far less dependent on Chinese or Russian antimony. It would essentially become the only domestic antimony mine and one of the largest antimony sources outside China. This is why Stibnite is often cited as a strategic asset; Perpetua touts it as “the nearest-term solution available to meaningfully counteract China’s dominance of the antimony market”. As mentioned earlier, the project achieved a major milestone with a favorable Record of Decision in January 2025 – meaning the Forest Service found its plan acceptable after an 8-year environmental review. The FAST-41 listing for Stibnite is somewhat ceremonial at this point (since the final permit was issued), but it underscores the project’s priority status. The mine still faces some opposition from environmental groups concerned about water quality and habitat in the Salmon River headwaters, as well as the perpetual issue of a large open-pit mine in a remote ecosystem. However, Stibnite’s case is helped by the fact that it includes an extensive reclamation plan to clean up historical mining pollution at the site (a legacy of World War II-era antimony and tungsten mining there). Perpetua has essentially packaged the project as both a mining venture and a restoration effort and it will remove old tailings and restore fish passage for salmon as part of its operations. This has won it some local support. With permits in hand and federal backing, Stibnite is now seeking construction financing – notably it has an Eximbank letter of interest for $1.8 billion in debt funding. If financing is secured, construction could start, making antimony supply disruptions a little less threatening in a few years. In sum, antimony’s inclusion in the fast-track list highlights the security dimension of critical minerals: it’s not just about EVs and green tech, but also bullets and missiles. The Trump administration’s emphasis on defense supply chains dovetails with this – ensuring a stable domestic antimony supply is as much about munitions as it is about industrial uses.

Metallurgical coal (met coal), on the other hand, is critical for a foundational industry: steelmaking. Met coal (especially high-grade hard coking coal like that mined in Alabama and West Virginia) is an essential feedstock for blast-furnace steel production – it’s turned into coke, which reduces iron ore to iron metal. While coal in general is often maligned (for its climate impacts when burned in power plants), metallurgical coal remains vital for steel, and steel is vital for infrastructure, vehicles, appliances, and defense hardware. The U.S. is actually a net exporter of met coal, supplying steel mills worldwide (especially in Europe and Asia) with some of the world’s highest quality coal. However, domestic steelmakers also rely on it, and having a robust local supply insulates them from swings in global coal markets. The FAST-41 list includes Warrior Met Coal’s mines in Alabama, specifically their planned Blue Creek mine expansion. Warrior Met Coal (NYSE: HCC) operates two longwall mines in Alabama’s Blue Creek seam, which produce a premium low-sulfur, high-quality coking coal. These mines currently produce about 7.5–8 million short tons per year of met coal. The company has been developing a new mine, Blue Creek No. 1, which could add another 6.0 million short tons per year of capacity once fully operational. This would be a roughly 75% increase in Warrior’s output, solidifying its position as a key global supplier of met coal. Blue Creek’s development requires federal leasing (the land is likely under federal minerals) and associated permits. By granting it FAST-41 status, the administration is signaling support for an expanded domestic coal supply for steel. Politically, this aligns with Trump’s promises to coal country and his mantra of “beautiful clean coal,” albeit here it is metallurgical coal (used in manufacturing) rather than thermal coal (for power generation).

From an industrial base perspective, one could argue met coal is quasi-critical. It isn’t on official critical mineral lists (because the U.S. has ample coal reserves and domestic production), but without it, we cannot produce new steel by conventional methods. (Steel recycling via electric arc furnaces reduces some need for met coal, but high-quality virgin steel for certain applications still depends on blast furnaces and hence coking coal). The Biden administration had taken steps away from coal – for instance, banning new coal leasing on some federal lands and not prioritizing it under critical minerals programs. Trump’s inclusion of Warrior’s project shows a different philosophy: that fuel minerals which underpin heavy industry deserve streamlined permitting too. In the global context, increasing U.S. met coal output could marginally reduce steelmakers’ dependence on Australian or Russian coking coal. It might also have trade implications where more export capacity for U.S. coal could help allies who face coal shortages (for example, after Russia’s Ukraine invasion, Europe sought alternative coking coal sources). However, environmental groups are likely to challenge coal mine expansions due to concerns about carbon emissions (even if the coal is for steel, its end-use still emits CO₂). Inside Alabama, local environmental and community concerns might include mine subsidence, impacts on waterways, or miners’ safety (Warrior was in the news due to a prolonged miners’ strike over labor conditions in 2021-2022). FAST-41 doesn’t override any of the safety or environmental laws, but it might compress the timeline for studies and decisions.

The main takeaway is that antimony and metallurgical coal exemplify the broader view of criticality beyond just hightech metals: one is critical for defense manufacturing, the other for core industrial manufacturing. The FAST-41 initiative explicitly recognized this by expanding its scope – indeed, an amendment to Trump’s executive order added coal to the list of target minerals. For antimony, fast-tracking the one major project (Stibnite) could eliminate a key strategic vulnerability, ensuring that the U.S. military’s need for antimony in ammunition can be met from Idaho instead of Asia. For met coal, accelerating Blue Creek will bolster an industry that provides high-paying mining jobs and feeds U.S. steel mills – aligning with Trump’s promises to reinvigorate mining and heavy industry. Both cases, however, will test how “streamlined” permitting interacts with environmental oversight. If agencies rush, they could face lawsuits (Endangered Species Act issues for Stibnite’s salmon habitat, or climate lawsuits for coal). Thus, achieving the intended benefits will require not just speed, but diligence to avoid legal pitfalls.

Production Impact of Key Fast-Track Projects

To put the above in perspective, the table below outlines the potential production capacity from several of these fast-tracked projects and their significance relative to U.S. demand or supply:

As shown, if these projects come to fruition, they would materially improve U.S. self-sufficiency in several key commodities. For copper, Resolution could single-handedly change the import balance. For lithium, a combination of Nevada and Arkansas projects would establish a domestic supply equivalent to a large fraction of our battery needs (though continued growth in EV demand means we’ll likely need even more beyond 2030). For antimony and potash, we’d be establishing domestic industries where we currently have essentially none – a big deal for economic and security reasons (e.g. potash is crucial for agriculture, and 94% is imported today ). The met coal addition secures the upstream of steelmaking, which in turn supports construction and defense (armored vehicles, ships, etc.). These numbers also underscore why the administration is eager to expedite permits: the faster these mines are built, the sooner their output can alleviate supply chain vulnerabilities. Delay by delay, year by year, is opportunity cost – either continued import dependence or missing out on high commodity prices.

Of course, not all these projects will necessarily reach their nameplate capacities or on the expected timelines. Mining is a risky business – technical challenges, financing hurdles, and market fluctuations can intervene. But the federal fast-tracking at least removes one major uncertainty: permitting timing. By providing clearer timelines, the initiative can help companies plan construction and investors model returns with more confidence. For instance, knowing that Michigan Potash’s permits might all be in place in, say, 2026 (as suggested by the 42-month construction timeline after final permits ) allows the company to line up capital and offtake contracts for its fertilizer. Similarly, Standard Lithium can signal to future customers (like battery makers or automakers) when its Arkansas lithium might be available. In commodity markets, expectations matter – credible signals of new supply can temper price spikes and discourage hoarding. In this way, the FAST-41 timelines being public is itself a market-facing signal: it tells the world that the U.S. expects these projects to advance on schedule, potentially easing long-term deficit fears in some commodities.

Thank you for reading The Mineral Strategist.