Conflict Minerals Deep-dive: PART I

Tin, Tantalum, Tungsten and DRC’s 3T Paradox. Background, Uses, Importance, Key Miners and Traders, Supply Chain, Market Dynamics, Pricing, Regulations, Current Developments, Recent News.

In March 2025, the price of tin spiked to an eight-month high overnight. The catalyst was not a financial crisis or factory fire, but a rebel advance in a remote corner of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Alphamin Resources – which produces 4% of the world’s tin at its Bisie mine – halted operations as insurgents approached, sending London Metal Exchange tin prices to nearly $34,800 per tonne . This dramatic episode underscores the fragile link between high-tech supply chains and on-the-ground conflict. The metals in question – tin, tantalum, and tungsten, known as the “3Ts” – are ostensibly ordinary industrial inputs. Yet in eastern DRC, they’ve earned a more ominous label: “conflict minerals.”

What Are Conflict Minerals and Why the 3Ts Are Labeled As Such

“Conflict minerals” refer to specific natural resources that fund violence and instability when mined under certain conditions . In particular, tin, tantalum, tungsten, and gold sourced from the war-torn eastern DRC have been notorious for bankrolling armed groups during the region’s prolonged conflicts . Over the past two decades, numerous rebel militias and even units of the national army have competed to control mines or levy “taxes” on 3T miners. The profits from a bag of cassiterite (tin ore) or coltan (tantalum ore) have, at times, directly funded weapons and insurgencies.

The reason tin, tantalum, and tungsten earned the conflict tag (often alongside “blood diamonds” in the public consciousness) is tied to the geography of their deposits. These 3T ores are abundant in the Great Lakes region of Africa, especially in the eastern DRC provinces of North Kivu, South Kivu, and Maniema – areas that have seen chronic insecurity.

By the late 2000s, advocacy groups and the United Nations had documented how rebel warlords in the DRC were financing themselves through the 3T trade. For example, at the height of the DRC’s violence, the Bisie tin mine (now run by Alphamin) was generating an estimated $100 million a year for a renegade militia brigade through illicit taxation and smuggling . International outrage at such links led to the “conflict minerals” campaign, casting the 3Ts (and gold) as the culprits behind Congo’s wars.

Industrial Uses: Why the World Needs Tin, Tantalum, and Tungsten

Despite their local clout, the 3Ts are globally sought-after for high-tech and industrial applications. Tin, for instance, is the humble metal that makes modern electronics possible. Nearly half of global tin consumption – about 47% – goes into solder , the tiny beads that fuse together circuit boards in phones, laptops, and appliances. Tin’s properties (low melting point and ability to alloy with lead or silver) also lend it to use in coatings, plating, and glassmaking. Every time we charge a smartphone or start a car, we’re using tin’s role as the “glue” of electronics. Without tin solder, the tech industry would literally fall apart.

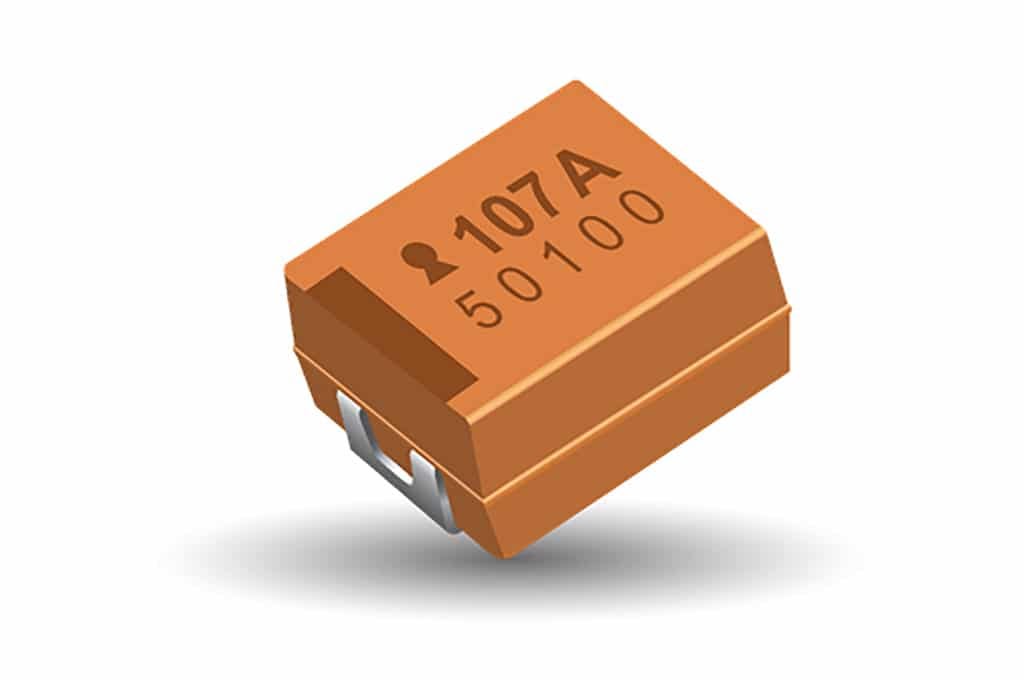

Tantalum, by contrast, is a ultra-specialized metal with superlative traits. It is exceptionally resistant to heat and corrosion, which is why it ends up in jet engines and surgical implants. But tantalum’s most ubiquitous use is in the tiny capacitors that regulate power in electronic devices. Roughly 70% of tantalum demand comes from the electronics industry – primarily for capacitor components in smartphones, computers, and automotive electronics . A typical smartphone contains only about 40 milligrams of tantalum , yet that speck is vital for making our devices small and power-efficient. Without tantalum capacitors, our phones and laptops would struggle to maintain stable voltages.

Tungsten (often known by its old name “wolfram”) is the brute of the trio – extremely hard, dense, with the highest melting point of any metal. Approximately 65% of the world’s tungsten is consumed in the form of tungsten carbide. Tungsten carbide is the backbone of cutting tools, drill bits, and machine tools that can slice through steel or bore into rock. It is what factory robots use to cut metal, what miners use to drill ore, and what surgeons use in some tools. The remaining usage is largely in steel alloys (≈14%) and specialty metal products (≈12%) – for example, tungsten gives hardness to high-speed steel and lends heat resistance to superalloys in jet turbines. Its high density also finds use in military armor and kinetic penetrators.

These uses highlight why the 3Ts are designated as “critical minerals” by many governments. They sit at the heart of supply chains for electronics, aerospace, automotive, and industrial tooling, meaning any disruption can reverberate widely. The economic importance of the 3Ts extends beyond their dollar market size – it’s about their utility in essential technologies and the lack of easy substitutes (you can’t just swap out tin in solder, or tungsten in a cutting bit, without major compromises). This importance sets the stage for the geopolitical dimensions of the 3T trade.

Economic and Geopolitical Importance of the 3Ts

For the DRC, the 3T minerals are double-edged: they are a source of national wealth and local livelihoods, yet have perpetuated a political nightmare. In pure economic terms, the 3Ts bring in more export revenue to the DRC than gold (according to pre-smuggling official stats), though they still lag behind the country’s giants like copper and cobalt . The DRC alone is estimated to supply around 30% of the world’s tantalum , when both official and illicit flows are considered. It is only a minor global supplier of tin and tungsten in comparison , but that “minor” status hides the fact that one Congolese mine (Bisie) can influence world tin prices, as we saw. Moreover, the 3T sector provides tens of thousands of artisanal mining jobs in a region with few other income options. By one estimate, 30,000–60,000 Congolese miners work in tin and tantalum mining across several hundred sites .

Geopolitically, control over 3T resources has been a microcosm of larger power struggles in Central Africa. Neighboring countries like Rwanda and Uganda have long been accused of profiteering from DRC’s mineral wealth by sponsoring proxy militias and enabling smuggling. For instance, Rwanda – a country with relatively modest tantalite reserves of its own – has paradoxically been one of the world’s top coltan exporters for the past decade . In 2023, Rwanda officially exported 2,070 tons of coltan compared to the DRC’s 1,918 tons , marking the fifth year in the last ten that Rwanda’s coltan exports surpassed its giant neighbor’s.

The reason is intuitive: a significant volume of DRC coltan is covertly funneled across the border and then re-exported as “Rwandan” . Such routing not only deprives the DRC of revenues but also provides Kigali with a lucrative stake in the critical minerals trade. A recent investigation by the UN and Global Witness found that up to 90% of 3T ore exports from Rwanda actually originate in the DRC via smuggling . This dynamic has turned the mineral trade into a regional chess match, implicating high-level politics – as seen in early 2024 when Rwandan-backed rebel group M23 seized control of Rubaya, one of the world’s richest coltan mining areas in North Kivu .

Internationally, the 3T supply is concentrated in a few key regions, which amplifies their strategic importance. China dominates tungsten, mining over 80% of global supply , and is a major player in tin (both as a miner and the top smelter of tin). Indonesia and Myanmar are critical tin sources as well. Tantalum production is more distributed (Australia, Brazil, Rwanda/DRC, Nigeria) but still relatively small- scale and vulnerable to disruption. The Western high-tech industry relies on a handful of smelters for processed tantalum powder and tin solder. Any geopolitical move – say, China imposing export controls on tungsten (which it announced in 2025 amid trade tensions) , or conflict flaring in the Kivus – puts high pressure on downstream manufacturers. Governments keep a close eye on them as critical raw materials for economic security. The DRC’s ability (or inability) to govern its 3T sector has repercussions from Washington and Brussels to Beijing and Tokyo.

Key Miners and Traders in the DRC’s 3T Supply Chain

Unlike the large industrial copper and cobalt mines in southern DRC, the 3T sector in the country is dominated by artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM). The typical 3T miner in Congo is a prospector with a shovel, not a multinational with a fleet of excavators. However, there are a few notable exceptions and big players:

Alphamin Resources – This Canadian-listed company operates the Bisie tin mine in North Kivu, one of the only modern, industrial-scale 3T mines in the DRC. Alphamin’s Bisie (known as Mpama North) is renowned as the highest-grade tin deposit in the world and produced over 17,000 tonnes of tin in 2024 . That output – a significant 4% of global tin supply – has made Alphamin a key supplier to international tin markets. The mine’s presence is also a rare case of formalization in a region otherwise filled with informal diggers. Yet, as we saw, even Alphamin isn’t immune to conflict – its operations were briefly suspended due to nearby militia activity . Still, Alphamin stands out as a model “conflict-free” source of tin within the DRC, and its success or setbacks send signals through the tin market.

Société Minière de Bisunzu (SMB) – A major Congolese-owned company, SMB runs the coltan mines of Rubaya in North Kivu, which are among DRC’s richest tantalum sources. SMB is (or was, until the recent M23 occupation) the largest formal coltan producer in Congo, operating under a government license and participating in traceability schemes. Rubaya’s output is considerable – UN experts noted the area accounts for around 15% of the world’s tantalum supply . Unfortunately, its very richness attracted the M23 rebels, who in 2024 ousted SMB’s control. M23 has since been exploiting Rubaya’s coltan, reportedly extorting a 15% “tax” on sales and smuggling the concentrate to Rwanda.

Artisanal Cooperatives and Local Traders – Beneath the few big names, the bulk of 3T mining is done by cooperatives of artisanal miners. These coops often work in designated artisanal zones (ZEA) or sometimes illegally on the concessions of larger companies. They use hand tools to extract cassiterite (tin) or coltan from pits and alluvial stream beds. Once ore is produced, a chain of local négociants (brokers) and comptoirs (export houses) comes into play. In towns like Goma, Bukavu, and Bukama, comptoirs purchase and aggregate 3T ores from hundreds of diggers. Some notable Congolese 3T exporters over the years have included entities like Panju, MMR, and Olive (among others), though names and fortunes rise and fall with the conflict’s ebb and flow. These local traders are the bridge between mine site and global market, usually responsible for tagging shipments as “conflict-free” (if they are part of traceability programs) and dealing with authorities for export permits.

International Traders & Smelters – On the global stage, a handful of traders and processing companies dominate the 3T supply chain downstream. One prominent example is a Luxembourg-based commodities trading firm. A 2024 investigation revealed a the trading firm bought 280 tonnes of coltan from Rwanda – volumes far above Rwanda’s own mine output – strongly indicating it was sourcing Congolese tantalum under a Rwandan label . Their purchases coincided with the surge of conflict coltan smuggled from DRC’s Masisi territory during the M23 rebellion . (They denied knowingly buying conflict coltan, but the paper trail of customs data and testimonies suggests otherwise .) Such traders then sell the concentrates to smelters and refineries – for tantalum, key processors are in countries like China, Austria, Kazakhstan, and the U.S.; for tin, major smelters are in Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, and China.

Smelters/Refiners are critical chokepoints: they transform raw ore into pure metal or alloys that can be used by component manufacturers. For instance, Malaysia Smelting Corporation (MSC) has historically been a large buyer of African tin concentrates (including from the DRC, sometimes via intermediaries). In the tantalum world, companies like H.C. Starck (Germany) or Global Advanced Metals (with plants in the U.S. & Australia) are notable, as is JX Nippon ( Japan) – these are among the refiners that produce tantalum powders for electronics. China, it must be noted, is a major smelting hub for all three Ts (especially tungsten and tin). Many Chinese firms also source from the DRC region, though often indirectly due to compliance concerns. An interesting player is the “LuNa” Smelter in Rwanda, which is a regional initiative to domestically smelt tantalum and tin – a sign that some 3T value-added is being captured locally in Africa (LuNa is now on industry-approved conflict- free smelter lists, processing both Rwandan and Congolese ore).

Supply chain from an artisanal DRC mine to a tech company’s product. Local intermediaries (“négociants” and export comptoirs) gather production which is then sold to international traders or directly to foreign smelters. These smelters/refiners produce the refined metals or powders that go into components (like solder, capacitors, or carbide tools), which are finally assembled into consumer and industrial products.

Notably, every link in this chain has been a focus of intervention to break the link with conflict – from cooperatives at mine sites to traceability tags handled by exporters, to audits at smelters and beyond.

Market Dynamics and Pricing Trends of the 3Ts

The 3T minerals may not be traded on flashy public exchanges (only tin has an LME contract; tantalum and tungsten trade in opaque minor-metals markets), but their price trends reveal the push-pull of supply and demand. Take tin: in the past few years, tin experienced a stunning rally followed by volatility. In late 2021, tin prices peaked around $39,000–50,000 per tonne (reports vary, with one indicator hitting $49,500 in March 2022). This was an all-time high, fueled by a pandemic-era electronics boom and supply bottlenecks (including COVID restrictions in Malaysia and a coup in Myanmar that choked off tin exports from the Wa region). Traders joked that “tin is the new gold” as prices nearly doubled in 2021. However, such peaks proved unsustainable – by late 2022, tin fell back on profit-taking and easing shortages . It seesawed again with the uncertainty in Congo. The March 2025 rebel scare bumped tin back above $34k, reminding the market that a single mine’s disruption can move global prices by >3% in a day

Tantalum, by contrast, trades in a quieter, contract-driven market – but it too has seen a notable uptrend. For much of the late 2010s, tantalum prices were relatively flat, hovering around $155–$160 per kilogram of Ta₂O₅ in concentrate form . This stability reflected a balanced market: steady demand from capacitor manufacturers, supplied by a mix of African mines and a few large Australian and Brazilian sources (as well as some recycling). Starting around 2021–2022, however, tantalum began creeping upward. By early 2025, Tantalum concentrate prices reached roughly $205 per kg (≈$204,660 per metric ton) in the U.S., a noticeable rise. The increase has been attributed to resurgent electronics demand (think 5G smartphones, IoT devices) and constraints in supply.

Tantalum’s market dynamics are unique: the absolute volumes are tiny (global output only a few million pounds), so a single buyer’s stockpiling or a single supplier’s hiccup can have a big impact on prices. Additionally, tantalum supply is somewhat inelastic – ramping up mining is slow, and there are no large- scale substitutes for its use in capacitors (ceramics and niobium capacitors exist but can’t fully replicate tantalum’s performance). This makes tantalum a strategic but vulnerable market. Any news of conflict affecting a major supplier (like the DRC or Rwanda) or of a major tech company increasing orders can send prices upward. Conversely, if global recession dents electronics sales, tantalum could soften quickly due to demand slack.

Tungsten prices, finally, have been steadily firming after a slump in the late 2010s. Tungsten is often priced in metric ton units (MTU) of Ammonium Paratungstate (APT), the primary traded intermediate. In 2023– 2024, APT prices hovered in the range of $300–$350 per MTU (roughly translating to ~$40–45 per kg of tungsten) – supported by recovering industrial demand and China’s strategic grip. Recently, China’s announcement in early 2025 to impose export controls on tungsten has added bullish pressure . Anticipation of Chinese export quotas caused tungsten prices to surge in May 2025, with concentrate prices in China reaching ¥154,000/ton (≈$22,000/t) and APT hitting ¥226,000/ton (≈$32,000/t) . For context, the U.S. import price for tungsten concentrate averaged around $86,200 per tonne in late 2024 , so any supply squeeze from China could significantly elevate costs for western consumers. Tungsten’s market is highly concentrated – outside China, producers in Vietnam, Russia, and Rwanda are notable but much smaller. Thus, geopolitics (trade wars, sanctions on Russia, etc.) and conflict (the DRC’s tungsten output is small, but Rwanda’s could be indirectly affected by regional instability) all feed into tungsten’s supply equation. Consumers such as machine tool makers and the defense industry are now anxious about securing non-Chinese sources, which could benefit projects in places like Australia or Spain in the future.

This concludes PART I of conflict minerals deep-dive. Part 2 will consist of regulations, global sourcing rules, impact, limitations, current developments, smuggling, certification, and the current 3T news.

This post is FREE so feel free to share and subscribe so we can continue posting quality deep dives like this one.

Very insightful, looking forward to part 2.